Were terracotta warriors real people?

The Terracotta Army of a Thousand Faces: The Mystery of the Terracotta Army’s “Real People” Revealed

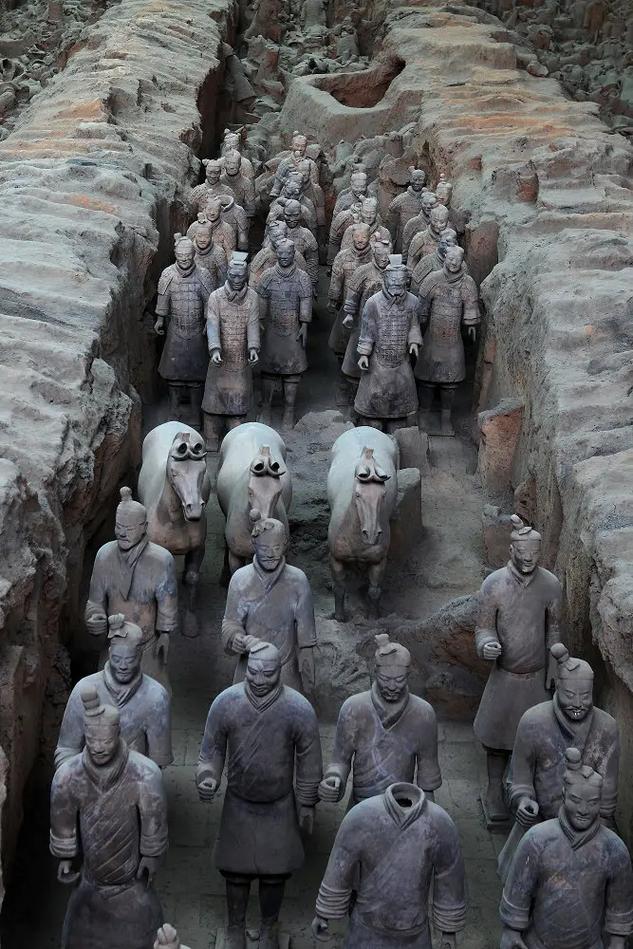

In 1974, farmers in Shaanxi, China dug up a broken clay human head while drilling a well. As archaeological work unfolded, an “underground army” of thousands of life-size terracotta warriors shocked the world. The soldiers had clear features and different appearances, and their hairstyles and palm prints could even be seen. Such a realistic image makes many people have questions: ** Are these terracotta warriors made of real people? ** What secrets are hidden in their production?

First, through a thousand years of “real confusion”

When tourists stand in front of the Terracotta Warriors pit for the first time, they are often shocked by the details of the terracotta warriors: some people have eyelashes painted on their eyelids, some people’s mouth corners are slightly upturned, and some people are wearing different earrings. Even more amazingly, archaeologists have discovered that **each terracotta warrior’s ear is uniquely shaped** – just like a modern human fingerprint. These features make people wonder: did Qin Dynasty craftsmen make these terracotta warriors against the faces of real soldiers?

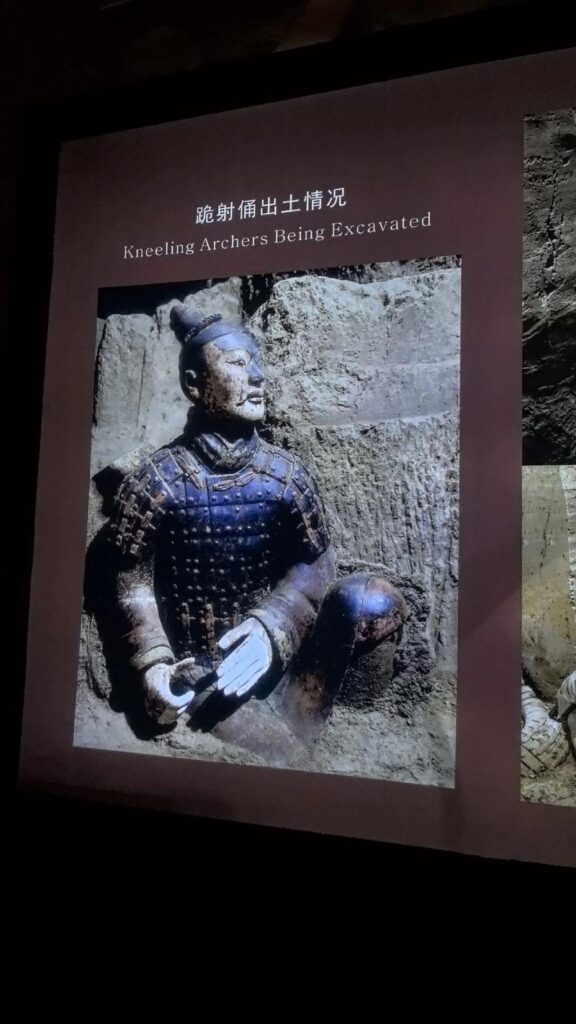

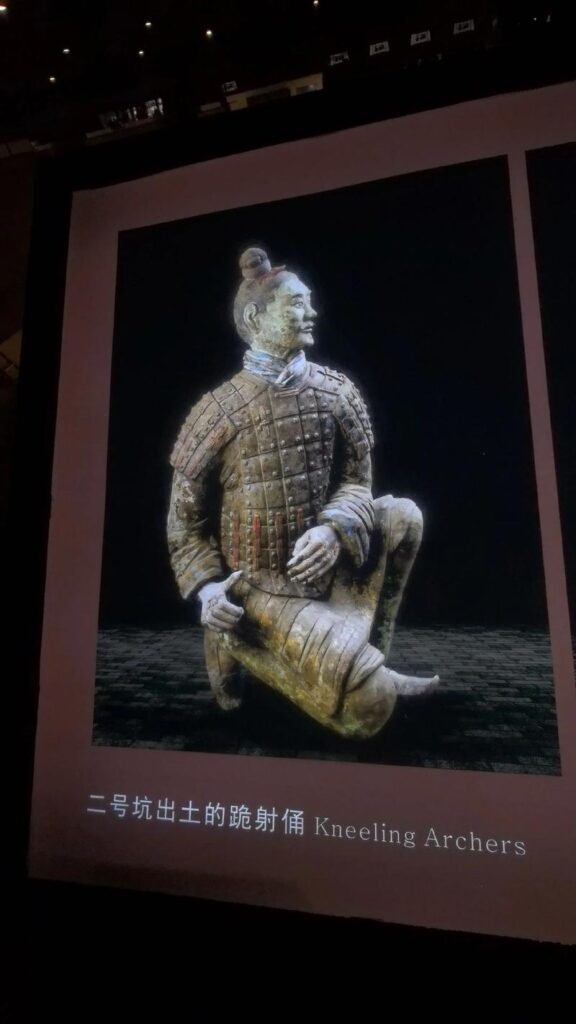

In fact, the interior of the terracotta warriors is a completely hollow terracotta structure. Through CT scans and analysis of broken pieces of pottery, scientists confirmed that the terracotta warriors were made of fired clay and did not have any human tissue inside. But they are still amazingly realistic: the average height of the soldiers is 1.8 meters, 10 centimeters taller than the average Chinese at the time; the stomachs of the generals’ figurines are slightly bulging, displaying the physique of middle-aged generals; and the pin lines on the soles of the kneeling shooting figurines are clearly visible.

Second, the assembly line “artificial soldiers”

Qin Dynasty craftsmen with wisdom to solve the “mass production of personalized” problem. The Qin craftsmen solved the problem of “mass production and personalization” with their wisdom. They divided up the work like a modern factory:

1. **Modular production**: head, torso, limbs are made separately, and then assembled like building blocks. But the craftsmen add personalized details to each part, such as changing the shape of the beard or adjusting the angle of the brow bone.

2. face database: scholars through three-dimensional modeling found that the terracotta figurines face can be summarized as 8 kinds of basic face, and then through the pinch molding, carving combinations of hundreds of variations, such as the ancient “face recognition system.

3. Standardized accessories: armor, hair buns, shoes and other parts have uniform specifications, but through different combinations to form a diversity.

This “standardization + personalization” mode, so that the terracotta warriors not only to maintain the unity of the army, but also to avoid uniformity. As archaeologists say, “This is not a replica of a real person, but the creation of an idealized world of soldiers.”

Third, why not use real people to accompany the burial?

Before the emergence of the Terracotta Warriors, the brutal tradition of burying live people did exist in ancient China. Martyrdom was common in the tombs of Shang Dynasty aristocrats, and the concept of “serving the dead with the living” still existed during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods. But Qin Shi Huang’s choice demonstrates the progress of civilization:

Historical Turn: In 384 BC, Qin officially abolished the system of human martyrdom and replaced it with terracotta and wooden figurines. The Terracotta Warriors are the culmination of this change.

The political elephant in the room: the use of terracotta armies instead of human guards not only demonstrated the authority of “commanding thousands of troops after death”, but also prevented the massacre of soldiers from triggering public discontent.

Technological confidence: The Qin believed that their pottery technology was sufficient to create “immortal” armies. The names of the craftsmen found inside the terracotta figurines (e.g. “Xianyang Wu”) are a reflection of this pride in their craftsmanship.

Interestingly, the Qin’s choice contrasts with that of ancient Egypt. Egyptian pharaohs used mummies to preserve their real bodies, while Qin Shi Huang used clay to build a virtual world – perhaps reflecting the different understanding of “immortality” between East and West.

Fourth, modern science and technology to crack the Millennium Puzzle

In order to thoroughly answer the “real people doubt”, scientists have used a variety of technical means:

1. material analysis: X-ray fluorescence detection shows that the terracotta figurines and the composition of the Lishan clay is completely consistent, to exclude the possibility of mixing human ashes. 2.

2. Internal probing: A miniature camera entered the terracotta figurine’s body and did not find any bones or organs remaining, only clay scaffolding to support the structure.

3. DNA testing: Samples of pigment layers taken from the surface of the terracotta figurines revealed only mineral components, with no traces of human or animal genes.

In 2012, a groundbreaking study revealed the “inhuman nature” of the Terracotta Warriors: by comparing the facial features of 800 terracotta warriors, the computer found that **all faces deviated from the proportions of real people’s faces** – with slightly larger eyes and a higher bridge of the nose, just like the “beautification” of modern animated characters. like the “beautification” of modern animated characters.

V. Artistic wonders more real than real people

Although the Terracotta Warriors are not real people, they carry more historical information than the remains of real people:

Living history files: hair bun style reveals that the soldiers came from different regions (Chu people left Ò hair, Qin people right Ò hair); the number of pieces of armor to show the rank of the military.

Frozen moments: some terracotta figurines have the indentation of a weapon’s wooden handle remaining in the lines of their palms, as if they had just put down their spears; the hem of a general’s armor is stained with “virtual mud spots”, reproducing the scene of marching in the rain.

Lost skills: The hollow design in the arms of the terracotta figurines prevented them from blowing up when they were fired, a technique that was lost after the Qin Dynasty and not mastered by modern industry until now.

As the restoration experts say, “Every detail of these terracotta figurines speaks; they are not real-life soldiers, but they tell the story of the Qin Dynasty more realistically than real people.”

Conclusion: The Glory of Humanity in Clay

When we gaze at these 2,000-year-old clay faces in the museum, what is really striking is not whether they were made by real people, but how the ancient craftsmen infused the clay with their observation and reverence for human beings. Every fold of clothing, every strand of beard, are condensed respect for individual life – even if this life belongs to the virtual warrior.

Today, when 3D printing technology can perfectly replicate the human face, we are even more amazed at the miracle created by the Qin people with their hands: without using any real person, they made 8,000 faces immortal. This is perhaps the most touching quality of Chinese civilization: while respecting life, it transcends the boundaries of life and death with wisdom and art.