What was special about the Terracotta Army?

Time-traveling Qin Army: Uncovering the Five Unique Codes of Terracotta Warriors and Horses that Shocked the World

First, the “resurrection army” under the farmer’s hoe: the discovery legend that rewrites the history of archaeology

In the spring of 1974, Shaanxi farmer Yang Zhifa was digging a well on the arid land, and a hoe cracked open a secret that shocked the world – his shovel touched not only pieces of pottery, but also awakened an underground legion that had been dormant for 2,200 years. This dramatic beginning, like a scene from the “Raiders of the Lost Ark” movie, instantly put the Terracotta Army in the global media spotlight. What archaeologists then uncovered was a massive burial system covering more than 20,000 square meters, large enough to fit three American football stadiums.

The discovery rewrote the course of Chinese archaeology: the military empire of Qin Shi Huang, originally thought to be a myth or legend, was suddenly brought to life in figurative form. What’s even more shocking is that the more than 8,000 terracotta figurines that have been unearthed are only the tip of the iceberg of the entire tomb system – remote sensing technology has revealed that there may be another 600 untouched relics buried underground. This shocking experience of “discovery is disruption” made National Geographic list the Terracotta Warriors as “the greatest archaeological discovery of the twentieth century”.

War machine with thousands of faces: decoding the military code of the Qin Empire

When visitors stand on the viewing platform of Pit 1, the first thing that strikes their vision is the more than 6,000 warrior figurines arranged in 38 columns. These ceramic soldiers, with an average height of 1.8 meters (15 centimeters taller than the average Chinese male at the time), unfolded in classic battle formations such as the Vanguard Formation and Fish Scale Formation. Each combat unit is precisely configured with crossbow, infantry, and vehicle soldiers, and their tactical combinations are so subtle that even professors from West Point made a special trip to study them.

What really amazes archaeologists is the uniqueness of each terracotta figurine: analyzed through 3D modeling technology, more than 200 templates of facial features have been identified, ranging from the single-eyed Guanzhong Hanzi to the bearded Northwestern warriors, and even the presence of suspected Mediterranean faces. The number of knots on the soldiers’ armor and the way their hair is woven in a bun all conceal the code of military rank – for example, the flat bun of a cavalryman represents the need for fast and mobile combat, while the crossbill of a general figurine is a symbol of bravery. This perfect combination of standardized production and personalized craftsmanship did not reappear in Europe until after the Industrial Revolution.

Third, the technological revolution of bronzes: black technology two thousand years ahead of the West

The bronze weapons sleeping in the array of terracotta figurines unveiled an even more amazing technological code. The 40,000 pieces of arrowheads unearthed were tested by electron microscope with an error of no more than 0.02 mm, a level of standardized production comparable to modern bullet manufacturing. What is even more incredible is that the bronze swords treated with chromium salt oxidation are still chilling after 2,100 years of burial – this anti-rust technology was not patented by the Germans until 1937.

The archaeological team found the earliest standardized coding system in crossbow components: each part was engraved with the craftsman’s code and the assembly serial number, ensuring that any damaged part could be quickly replaced. This concept of “modular production” predates the production line of the American Ford car by 2,100 years. Laboratory analysis also shows that the surface of the figurines was originally coated with vibrant colors of purple, blue, and gold extracted from minerals, including China’s unique formula of cinnabar and malachite, a pigment technique that eventually influenced Renaissance European painting via the Silk Road.

Unfinished Eternal Project: Historical Moments Frozen in the Clay

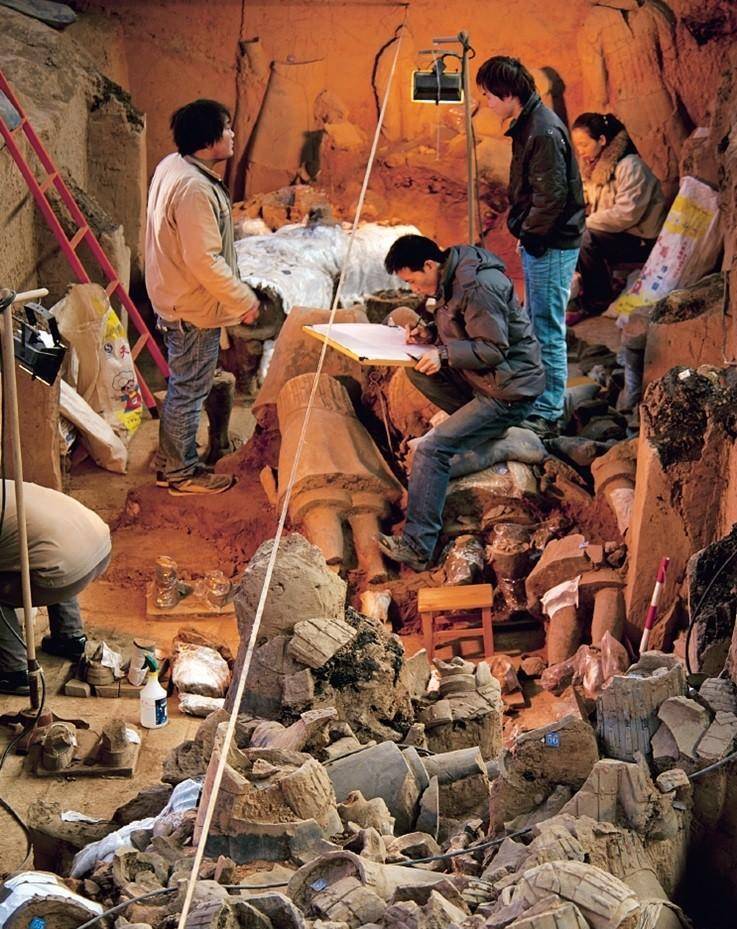

Scanning the interior of the terracotta figurines, archaeologists found a large number of fingerprints of the craftsmen – these traces of handwork from 2,200 years ago suddenly gave the cold clay a warmth. The inscription “Xianyang Gongji” found on the legs of the terracotta figurines reveals the code of operation of the Qin military industrial system: teams of craftsmen from the capital Xianyang rotated quarterly, and a strict quality traceability system was implemented in each workshop.

Most striking of all is the array of unfinished terracotta figurines: among the semi-finished products found in Pit 5, some of the soldiers were molded with only the outline of their torsos, and some of the warhorses had not yet been fitted with tails. These works of art, frozen in the making, seem to have been frozen in time in the fall of 210 B.C., when Emperor Qin Shi Huang suddenly died. Modern engineers have calculated that it would have taken at least 700,000 people working continuously for 38 years to complete the entire mausoleum system – the equivalent of mobilizing 1/3 of the adult male population of Qin at the time.

V. Living Cultural Heritage: From Shaanxi Farmland to the World Stage

Today, the Terracotta Warriors have become special messengers of civilization dialogue: NASA scientists have improved the coating technology of space probes by studying the painted pigments of the terracotta warriors; Hollywood special effects teams have used 3D scanning technology to replicate the terracotta warriors and create a more realistic scene of the ancient legions for The Mummy 3. Of the more than 5 million visitors each year, 37% come from Europe and the United States, and the #TerracottaSelfie hashtag they create on social media gives new life to the ancient civilization.

When you find the detail of eyelashes pressed into the eyes of terracotta figurines by artisans with combs, and the deliberate fingerprint marks on the hems of the robes, you understand why Time Magazine called it “man’s greatest attempt to fight time by hand.” This never-ending legion of clay is both a mad fantasy of Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s conquest of death and the common cultural heritage of all mankind – it tells us that true eternity lies not in gold and precious stones, but in the codes passed down from civilization to civilization.