What was the mercury in the Terracotta Army tomb?

The Mystery of Mercury: The Rivers of the Qin Empire Buried Deep Underground

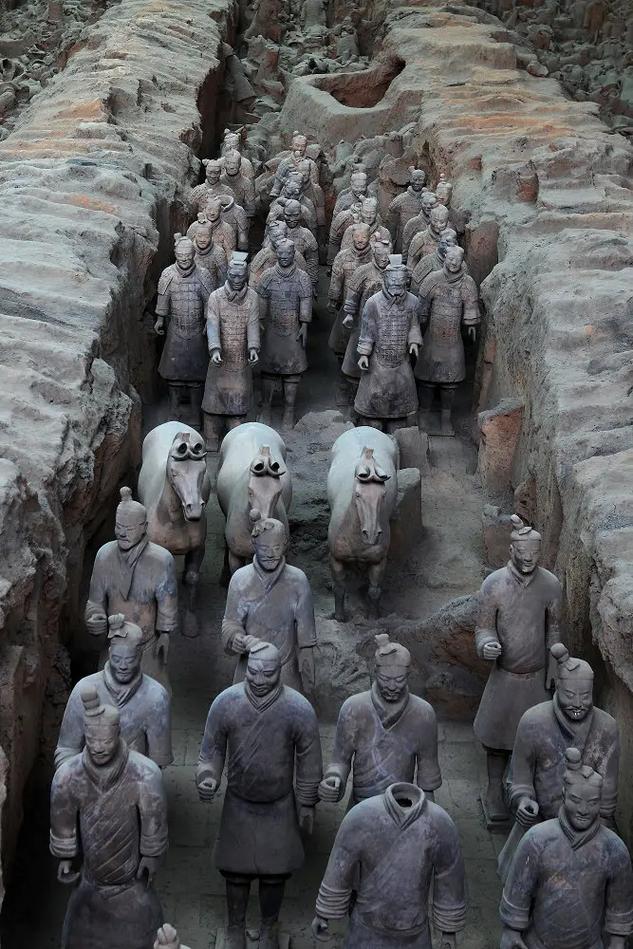

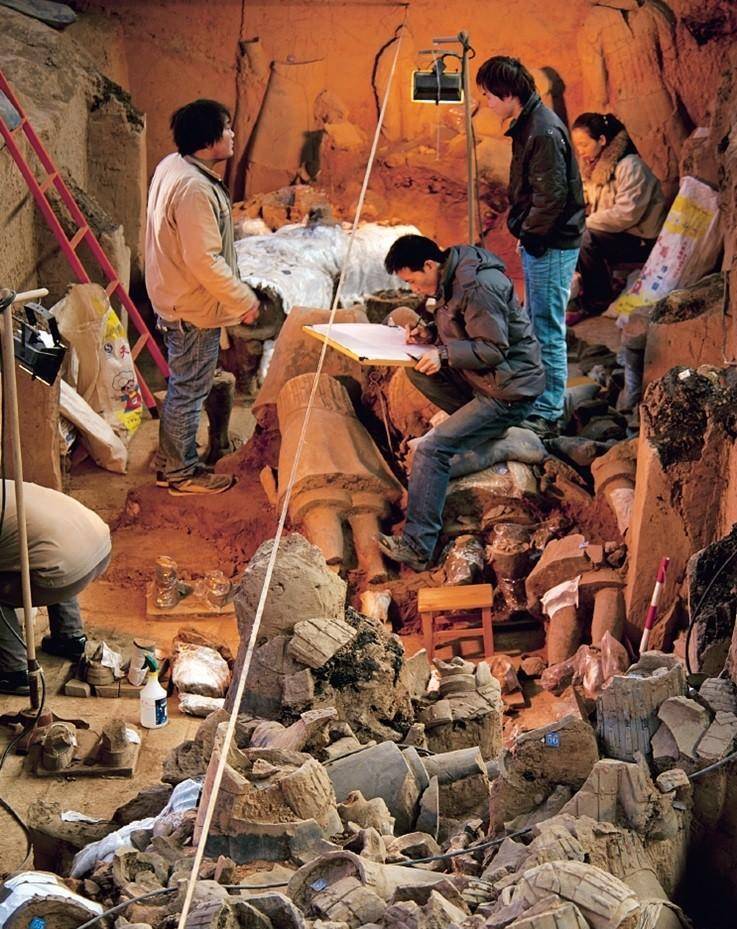

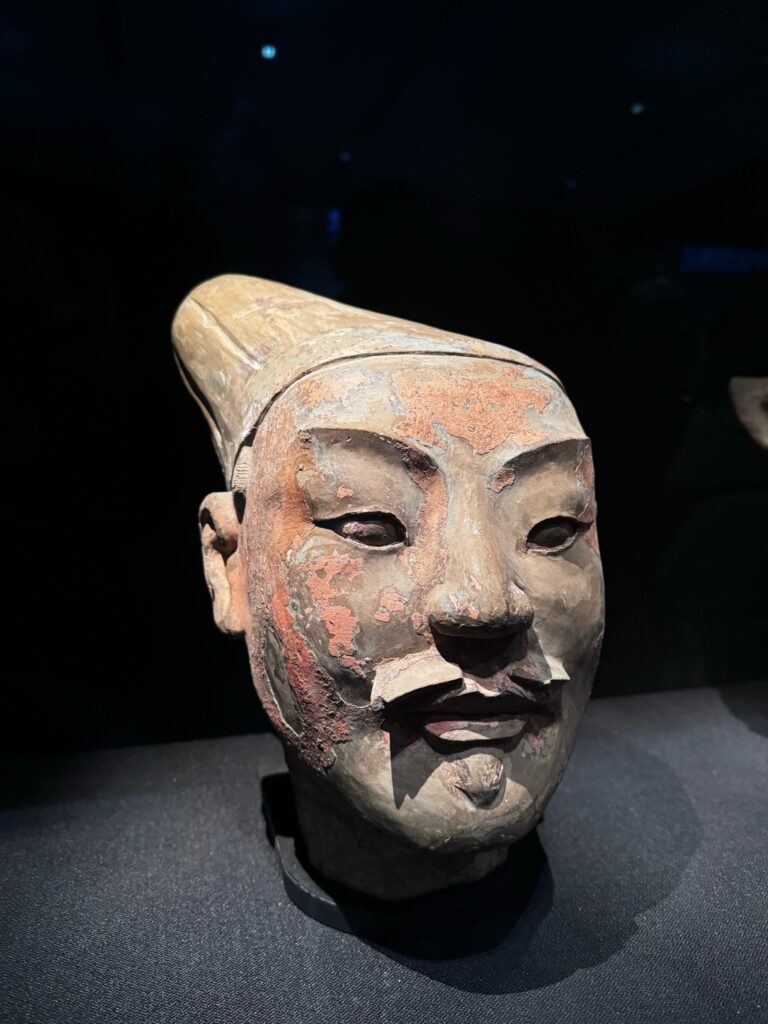

As you step into the Xi’an Terracotta Army Museum, the thousands of silent clay soldiers, with their majestic presence frozen in time for a thousand years, silently tell the world of the extraordinary talent and ambition of China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang. However, this grand military array is merely a small part of the vast puzzle that is Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum. The true core lies in the underground palace of Qin Shi Huang, which remains sealed and unexplored to this day. Among the countless legends surrounding the underground palace, the most captivating is the secret of the “mercury rivers” said to flow within it.

Mercury: The Liquid Silver

Mercury, known to the ancients as “mercury,” is the only metal that remains liquid at room temperature. Its surface shimmers like flowing silver, yet it harbors deadly toxicity. As early as the Warring States period, ancient Chinese people had already understood the properties of mercury and widely applied it in the alchemical furnaces of alchemists—they were obsessed with the belief that this mysterious liquid metal could be used to refine the elixir of immortality. At the same time, people also discovered that mercury possesses powerful and antibacterial properties, making it a precious material for preserving corpses in ancient tombs.

The Mercury Rivers of History

The most authoritative and intriguing account of the internal structure of Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum comes from the great Han Dynasty historian Sima Qian. In his immortal masterpiece, The Records of the Grand Historian, he described the underground palace thus: “Mercury was used to represent rivers, seas, and oceans, with mechanisms to circulate the liquid.” In just twelve words, he paints a breathtakingly surreal scene: the First Emperor’s coffin floats atop an artificially constructed vast “territory,” with the empire’s map meticulously simulated in mercury beneath his feet—the meandering Yellow River, the surging Yangtze River, and even the vast East Sea all “flow” in the form of mercury in the mysterious, dark underground world. Even more astonishing are the four characters “mechanically circulating,” suggesting that Qin-era craftsmen may have utilized intricate mechanical devices to keep these “mercury rivers” in a state of continuous flow, mimicking the awe-inspiring spectacle of nature’s ever-flowing rivers.

Modern scientific validation

For centuries, this passage from the Records of the Grand Historian was often regarded as romantic literary imagination. However, modern science has finally provided strong support for Sima Qian’s account.

In the early 1980s, Chinese researchers conducted pioneering mercury content measurements in the soil of the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum’s mound (the massive burial mound). The results were shocking: the mercury content in the central area of the mound was abnormally high, far exceeding that of the surrounding soil by dozens of times! This was like a silent yet loud signal, indicating that there was indeed a massive amount of mercury vapor continuously and slowly escaping upward from the depths of the underground palace.

In the 21st century, more advanced remote sensing and geophysical exploration technologies revealed deeper secrets. Scientists clearly detected a strong mercury anomaly zone within the underground palace, covering an area of approximately 12,000 square meters (equivalent to nearly 30 standard basketball courts)! Its distribution pattern astonishingly aligns with the ancient Chinese water system layout—the highest mercury concentrations are concentrated in the northeast, resembling the location of the Bohai Sea; while the mercury “rivers” in other areas wind and twist, resembling the major rivers of the Qin Empire. These cold scientific data, transcending over two thousand years of historical fog, provide a solid and credible footnote to Sima Qian’s grand narrative of “mercury flowing like a hundred rivers.”

The Source and Cost of Mercury

Where did such a massive quantity of mercury come from? Historical records point us in the right direction. Emperor Qin Shi Huang had shown special favor to a legendary female merchant from the Ba-Shu region (present-day Chongqing area) — the widow Qing. Her family had generations of experience operating the largest cinnabar mine (mercury sulfide ore, the primary raw material for mercury extraction) at the time. It is easy to imagine that to meet the enormous demands of constructing the underground palace, the empire must have mobilized immense administrative power and resources, driving countless artisans to toil in the deep mountain mines of Ba Shu to extract cinnabar ore, which was then transported via arduous and perilous routes to the Lishan Mausoleum complex. At the tomb construction site, artisans worked day and night to smelt the ore, extracting liquid mercury, which was then injected into the pre-designed “river” system deep within the underground palace. This process alone was a massive national engineering project.

The deeper meaning of mercury: immortality and protection

Why did Emperor Qin Shi Huang spare no expense or manpower to inject tons of mercury into the underground palace? His intentions were profound and complex:

Simulating the Cosmos, a Symbol of Eternal Rule: Using mercury to construct rivers, lakes, and seas, replicating the vast empire he conquered and ruled during his lifetime, this was the ultimate expression of Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s belief that “death is no different from life.” He sought to maintain control over this mercury-forged territory even in the afterlife, a desire for power and pursuit of eternity that is truly awe-inspiring.

Powerful: The mercury vapor emitted by mercury is extremely toxic but highly effective in killing bacteria and insects. Emperor Qin Shi Huang understood this well and sought to utilize mercury’s to create an eternal resting place impervious to the passage of time, safeguarding his physical body from decay (at least according to the beliefs of his era).

A deadly anti-theft barrier: Mercury’s toxicity was also given another practical and deterrent function—anti-theft. The mercury vapor permeating the underground palace itself served as a lethal chemical barrier. Folk legends added a mystical touch: if tomb raiders entered, the triggered mechanisms would not only activate crossbows and hidden arrows but also stir the mercury rivers, releasing deadly toxic mist. This dual protection reflects the meticulous and even ruthless wisdom of the designers.

Unresolved Mysteries and Eternal Awe

Although modern technology has confirmed the existence of mercury in the underground palace, its exact total volume, complex distribution patterns, and the specific mechanisms of the “mechanical pumping” devices that drive its flow remain shrouded in mystery. The limitations of current protective technologies and the significant risks to staff and the environment mean that active excavation of the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum remains off-limits in the foreseeable future. The mercury rivers buried deep underground, along with the core secrets of the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum, will continue to lie silent in the dust of time, remaining an enigmatic and alluring unsolved mystery in the history of human civilization.

When modern scientific probes quietly touch the dark realm at the foot of Mount Li, and cold instruments capture the silent diffusion of mercury vapor, the magnificent vision described by Sima Qian two thousand years ago—“mercury as rivers, seas, and oceans”—transforms from a vague legend into a breathtaking historical reality. These liquid silver metals are no longer merely the ancient people’s pursuit of immortality; they are more like a window—through which we can glimpse the Qin Empire’s awe-inspiring organizational capabilities, extraordinary engineering wisdom, and Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s almost obsessive ultimate desire to control both the present world and eternal life after death.

These buried rivers of mercury are a liquid monument to the material and spiritual power of the Qin Empire. They silently narrate how a long-vanished dynasty replicated its vast territorial map in the dark underground with its colossal strength. They are both a difficult attempt at immortality and a toxic declaration standing between time and tomb raiders. Even today, the mercury’s pulse still faintly beats beneath the earth, continuing to awaken humanity’s deepest reverence and curiosity about ancient splendor and the ultimate fate of life, through both scientific evidence and unsolved mysteries.