What was the original color of the Terracotta Army?

Fading Legions: Uncovering the Secret of the Terracotta Warriors’ Thousand-Year Colors

In 1974, fragments of terracotta clay inadvertently unearthed by a farmer drilling a well in Shaanxi Province brought the Terracotta Warriors and Horses of the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor, which had been dormant for more than 2,000 years, back to life. When archaeologists carefully cleaned out the first complete terracotta warrior, they were shocked by the sight in front of their eyes: not only were the life-like features of this life-size warrior, but the surface of the broken pieces of ceramic was still covered with bright red, blue, green and other color blocks. This discovery overturned the world on the “gray and yellow terracotta army” inherent impression – the original, these are known as the “eighth wonder of the world” terracotta warriors, initially a colorful underground army.

First, the faded truth: when the millennium painted meets the modern air

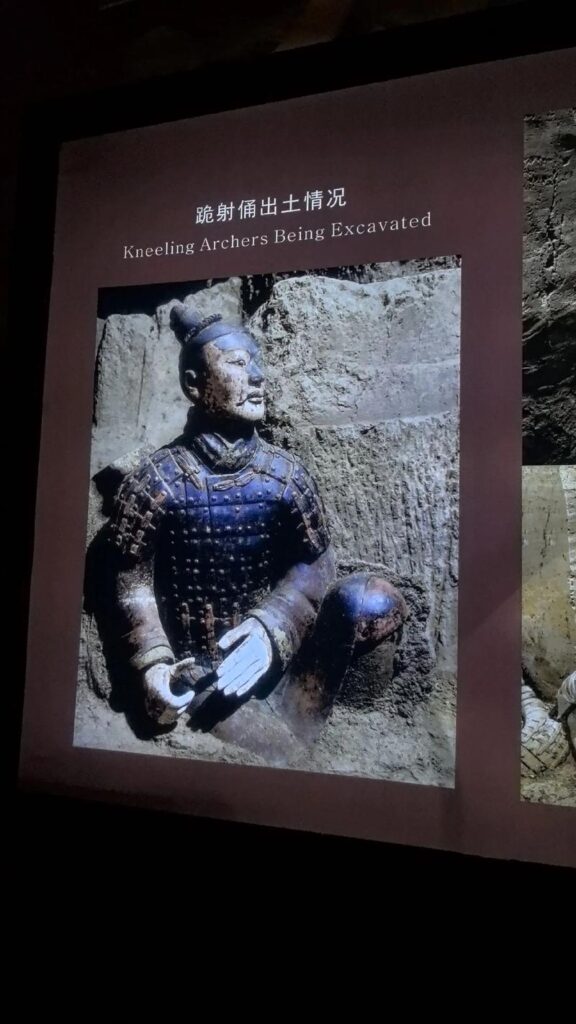

In the northwest corner of the mausoleum of the first emperor of Qin Shi Huang pit, archaeologists have found a preserved a large area of painted kneeling shot terracotta warriors. Its armor on the vermilion armor and pink and purple ties form a sharp contrast, the cuffs can even be seen repeatedly dyed gradient effect. However, such a sight is fleeting. When most terracotta figurines are unearthed, the layer of pigment adhering to the surface will be curled due to water loss within 15 minutes, and eventually flake off like an eggshell. Microscopic analysis revealed that Qin Dynasty craftsmen first applied raw lacquer as a primer to the terracotta tires, and then laid down mineral pigments. This process allows the colors to remain vibrant after 2,000 years of subterranean humidity, but the lacquer rapidly ages and cracks when it encounters dry air, causing the surface pigments to collectively “defect”.

In the laboratory, scientists collected tens of thousands of pieces of pigment residue like a jigsaw puzzle. They found that: terracotta figurines were mostly powdered white, symbolizing the aesthetic of “skin like cream”; armored warriors mostly used ochre to represent leather armor; and the edges of the armor of high-ranking officers were decorated with mysterious purple patterns. The most amazing thing is the analysis of the composition of the purple pigment – this kind of precious color of the Western Roman Empire at that time with the bone snail gland production, in the Qin Terracotta Warriors is actually synthetic copper barium silicate, this technology until the 20th century by the German chemists to re-invent.

Second, the color behind the hierarchical code

when the digital restoration technology will be faded terracotta figurines re “makeup”, a shocking visual system gradually clear. Ordinary soldiers wore green or red robes, centurion-level officers would be in the collar, sleeve edges embellished with purple trim, the armor of the general figurines are covered with blue and purple geometric decorations. This color hierarchy is an interesting contrast to the record in the Records of the Grand Historian, which states that “the clothes, banners, and flags were all black” – although the Qin dynasty used black as the national color, the army built up a strict hierarchical order through colorful markings.

In the latest excavated figurines of the imperial hand of the nobility in pit 8, archaeologists found more complex color combinations: indigo headscarves with vermilion sashes, ochre-yellow robes with malachite-green borders, and jade ornaments with traces of gold tracings at the waist. This kind of ornate decoration that goes beyond practical function suggests that Qin Dynasty craftsmen had mastered the aesthetics of complex color matching. The alternating ultramarine green and orpiment on the bridle of the ceramic horse is a perfect match for the color matching theory of “green and white next to red and black next to black” in the “Records of the Examiner”.

When Eastern color spectrum meets Western civilization

Compared with the sculpture art of the Mediterranean world in the same period, this kind of color application shows the unique wisdom of the East. While the ancient Greeks used pure white marble to pursue ideal beauty, the Qin terracotta warriors used realistic paint to build an underground universe; the Romans used mosaics to collage eternity, while the Qin used mineral pigments to solidify moments. In the mural painting fragments unearthed at the site of Xianyang Palace, scientists also found the same pigment formula with terracotta figurines, indicating that the Qin Dynasty had established a cross-trade color management system.

German experts in heritage conservation have conducted experiments: painted layers reproduced with Qin Dynasty techniques can remain colorfast for 2,000 years in the water table environment of Mount Li, but can only survive for 72 hours in the modern atmospheric environment. This contrast dramatizes the dilemma of heritage protection – we are eager to show the original appearance of cultural relics, but also had to race against time. Today, the new silicone reinforcing agent can make the new paint layer to slow down the aging, multi-spectral imaging technology can “see” the naked eye can not distinguish the color molecules, 3D printing is to make the faded terracotta figurines in the virtual world to regain their luster.

Standing next to the Terracotta Warriors pit, when tourists marvel at the neatly arrayed terracotta army, it may be hard to imagine how brilliant these “gray-faced” warriors once were. Those fading colors are not only a testimony to the skills of ancient craftsmen, but also a visual key to decode the spiritual world of the Qin Empire. In the collision of science and technology and humanities, we gradually understand that the fleeting purple color is not only a miracle in the history of chemistry, but also the most beautiful footnote to the eternity of an ancient civilization.