How many slaves built the Terracotta Army?

Who built the Terracotta Army? The ordinary people behind the vast army

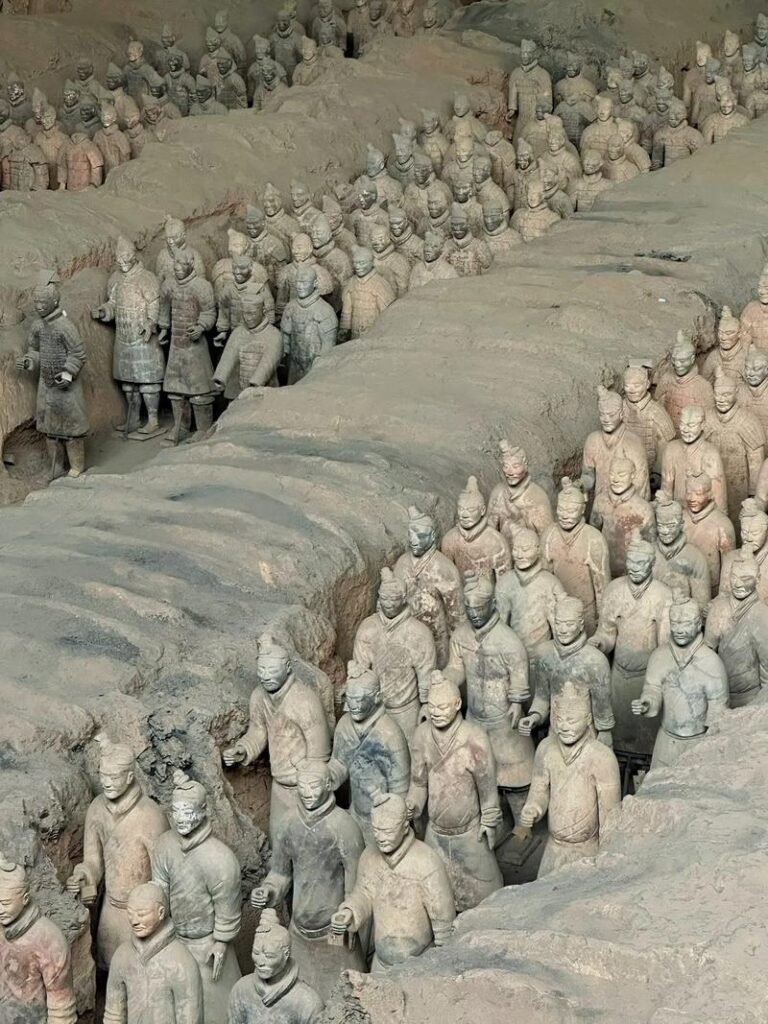

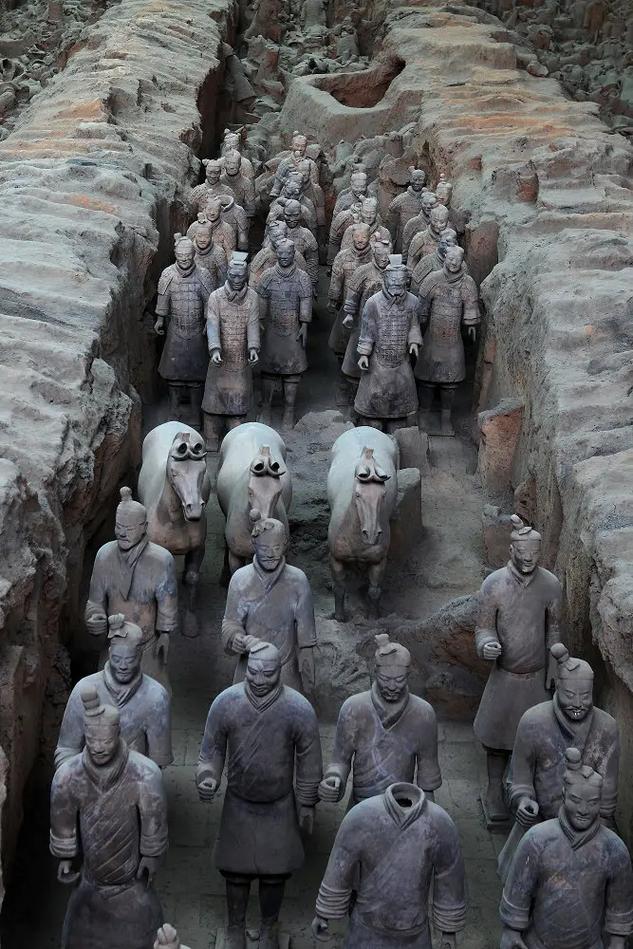

Standing before the Terracotta Army pits in Xi’an, you can’t help but be awe-struck by the thousands of life-sized clay soldiers, horses, and chariots. This massive “underground army” is hailed as one of the Eight Wonders of the World. But have you ever wondered: Who built such an enormous project? And what kind of people were they?

I. Unparalleled Scale: The Labor of 700,000 Hands

The construction of Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum and the Terracotta Army was one of the largest engineering projects in China over 2,000 years ago. According to historical records, during the peak of construction, nearly 700,000 people were mobilized! The entire project spanned approximately 39 years.

Imagine this: at the time, China’s total population was only around 20 million. This means that, on average, one out of every 25 to 30 people participated in this project! This number is truly staggering.

So, who were these 700,000 people? They primarily came from several groups:

1. Criminals and prisoners of war: After Emperor Qin Shi Huang unified China, he defeated many other states and captured numerous prisoners, who were sent to the construction site to work.

2. Ordinary citizens: The laws of the Qin Dynasty were very strict. If farmers or other commoners failed to complete the state-mandated labor tasks on time, they would be punished by being sent to build the mausoleum.

3. Skilled artisans: These were the core of the project. Craftsmen from across the country, including potters, carpenters, and metalworkers, were responsible for designing and creating the exquisite terracotta warriors, weapons, and chariots.

It should be noted that although the work was extremely arduous, most of them were not traditional “slaves” (like the completely unfree slaves of ancient Rome). Under the Qin Dynasty’s legal system, they were state-conscripted laborers with a complex status, but their circumstances were indeed very difficult.

2. Extraordinary Craftsmanship: The Artisans’ Masterpieces

What makes the terracotta warriors so astonishing is not just their sheer number, but how lifelike they are! Each terracotta warrior averages 1.8 meters (approximately 6 feet) in height, and each one has a unique face, hairstyle, clothing, and posture, resembling a real army.

How were these terracotta warriors made?

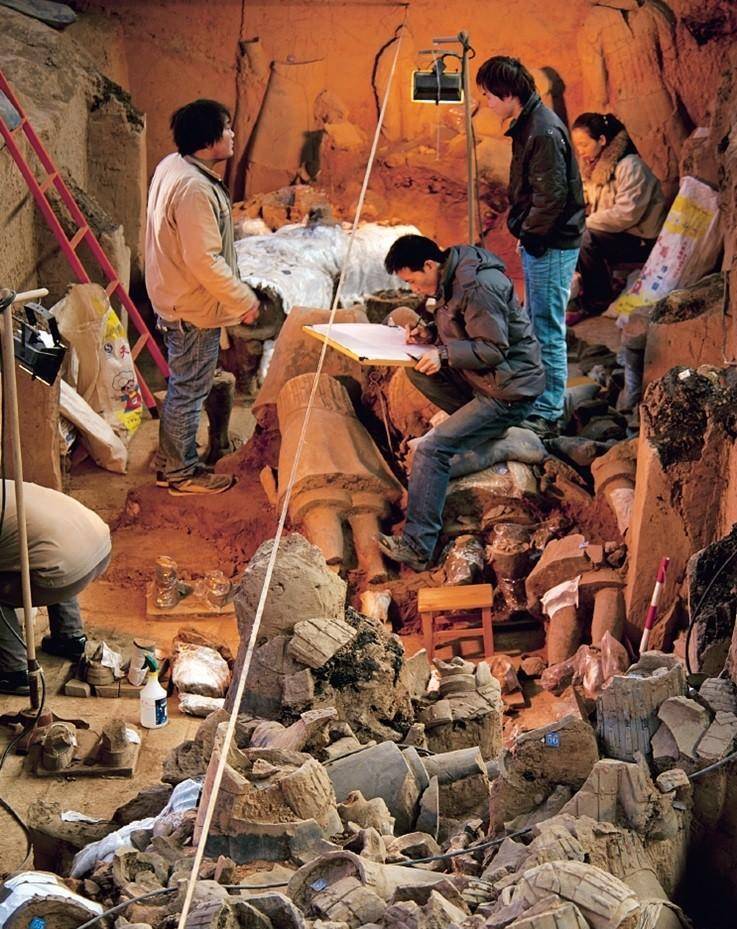

Separate production and assembly: The artisans were ingenious. They produced and fired the heads, bodies, arms, and legs separately before assembling them. This was akin to modern “assembly line” production, significantly improving efficiency.

Advanced weapon treatment: Thousands of bronze weapons were discovered in the terracotta warrior pits. Remarkably, many swords and arrowheads, despite being buried underground for over two thousand years, remain sharp and shiny with minimal rust. This is because the craftsmen of the time invented a special chemical treatment method (similar to applying a protective coating on the surface).

Precise firing: Firing such large clay figurines without cracking is extremely difficult. The craftsmen mastered advanced techniques to precisely control the kiln temperature within an appropriate range (approximately 950 to 1050 degrees Celsius).

Most interestingly, the Qin Dynasty implemented a “craftsman signature” system. Artisans were required to engrave their names or the mark of their artisan group on the terracotta figures or weapons they made. This was done to inspect quality, and if any issues arose, it would be possible to identify who was responsible. The names engraved on the terracotta figures serve as historical evidence, revealing that the Terracotta Army was not constructed by anonymous slaves but by organized, skilled artisan teams.

3. Civilizational Progress: From Human Sacrifice to Terracotta Warriors as Substitutes

The emergence of the terracotta warriors actually represents an important advancement: the abandonment of human sacrifice.

During the earlier Shang and Zhou dynasties, when kings or nobles died, they were often buried with living servants, slaves, or even relatives. This custom was extremely cruel.

During the early Qin Dynasty, there were still a few instances of human sacrifice. However, approximately 100 years before Emperor Qin Shi Huang, the Qin State had officially abolished the practice of human sacrifice.

It is said that Emperor Qin Shi Huang initially considered using thousands of young boys and girls as human sacrifices. However, his minister Li Si advised him, “Your Majesty, building the Great Wall has already caused great hardship for the people. If we also use human sacrifices, it may lead to major unrest!” Emperor Qin Shi Huang ultimately heeded this advice and decided to use terracotta warriors instead of live people.

The appearance of these terracotta warriors was modeled after the elite troops that had guarded him during his lifetime. The terrifying stories that “the terracotta warriors were made by wrapping live people in clay and then burning them” have been completely refuted by archaeological discoveries—scientists examined the broken terracotta figures and found **no traces of human bones inside**.

4. The Harsh Price: The Hardships of the Laborers

Although they were spared from being buried alive as sacrifices, the laborers involved in constructing the mausoleum still faced extremely harsh and dangerous living conditions:

Heavy Workload and Severe Punishments: From ancient letters and records discovered, it is evident that the laborers had to work with great care every day. If mistakes were made, such as damaging the paintwork, they would face severe punishments.

No guarantee of life: As Qin Shi Huang’s tomb neared completion, his son, Qin Er Shi (the second emperor), ordered the final group of artisans working in the underground palace to be sealed inside, effectively burying them alive to keep the secrets of the underground palace!

Harsh living conditions: The laborers lived in makeshift huts, suffered from food shortages, and received inadequate medical care when they fell ill. Archaeologists discovered laborer graves near the construction site, many of which contained skeletal remains showing signs of overwork, malnutrition, and injuries. Some of the victims died at a very young age.

History can be ironic. After the Qin Dynasty fell, the rebel leader Xiang Yu led his troops into the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum area and set fire to the terracotta warrior pits. The fire destroyed not only the clay figures but also the fruits of labor—the blood, sweat, and even lives—of countless workers who never returned home.

Remember those anonymous hands

So, who built the terracotta warriors? Nearly 700,000 ordinary people.

Among them were skilled craftsmen, farmers conscripted far from their homes, and unwilling prisoners of war. They were not the “slaves” vaguely recorded in history books, but real people who once existed. On those silent clay figures, archaeologists have even discovered the clear fingerprints left by the craftsmen of that era. These fingerprints are more real than Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s pursuit of immortality and can transcend time.

The Qin Empire has long vanished into the annals of history, but these ordinary builders, with their hands, wisdom, sweat (and even their lives), created a miracle that astonishes the world. What they left behind is not merely thousands of terracotta warriors, but an eternal testament to humanity’s pursuit of creation and yearning for dignity in the face of adversity. The next time you gaze upon the terracotta warriors, please remember the stories behind them.